Advent 3, Year A

Stir up your

power, O Lord, and with great might come among us; and, because we are

sorely hindered by our sins, let your bountiful grace and mercy speedily

help and deliver us; through Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom, with you

and the Holy Spirit, be honor and glory, now and for ever. Amen.

I

may be showing my inner orneriness here, but our reading today from James gets

on my nerves. “Be patient,” he intones in a preachy way. “Don’t grumble.” “Just

suffer quietly.” When I hear this text, I think of my teenage sister getting up

in my face and singing, “You better watch out, you better not cry,” every time

I got upset about something before Christmas. That was the last thing that this

four-year-old wanted to hear in the midst of a tragedy or a temper tantrum. “You

better not pout, I’m telling you why … Santa Claus is coming to town.”

I

don’t know about you, but if I’m feeling impatient, it sure doesn’t help to

hear some pious Bible verse asking me to be quiet about it.

You

children know how hard it is to be patient right before Christmas, don’t you? One

year, I couldn’t wait to get an expensive Madame Alexander doll in a pink

organza ball gown. Another year, I just knew that I could find the cure for

cancer as soon as I got a real, working microscope set. Another year, my hopes

rested on that stylish outfit from the fancy catalogue—the one that would make

my crush finally notice that I was alive. I was so impatient for these exciting

gifts that I would prowl around the house, peeking in closets and under beds, rattling

the packages under the tree and trying to lift up the pieces of tape without

tearing the wrapping paper. The days seemed so long until Christmas morning,

the waiting a torture.

And

then, of course, Christmas morning would come in all of its glory, and my

impatience would fade into disappointment. It wasn’t long before I put

fingernail polish “make up” on the Madame Alexander doll and marred her

beautiful face forever. The microscope set showed water bubbles under the slide

covers, instead of bacteria. And the boys still wouldn’t talk to me, even when

I wore my fancy dress. “Is that all there

is?” I would wonder with a sigh, my arms full of toys, and my eyes filled once

again with impatience for something new.

“Are

you the one,” the imprisoned John asks Jesus, “or are we to wait for another?” His

question is full of thinly-veiled impatience. I can imagine the wild and impetuous

John the Baptizer in prison, his camel’s hair robe in tatters and his long hair

sticking out in all directions. His strident preacher’s voice has turned to dark,

silent introspection. His head is down on his shaking knees, and his once-pointing

fingers hang limp at his sides. He had set out to bring his people closer to

the saving God of the swirling desert sands. He was impatient for the dawning

of a better age, an age of freedom from sin and from oppression. And yet,

here he is in prison—captive to the whims of a self-absorbed ruler and his greedy

courtiers. Where is cousin Jesus, in whom John has placed so much

hope? Why isn’t he doing anything about King Herod? Why doesn’t he use his

power now, before it is too late? What is he waiting for?

John

knows the well-known words of the prophet Isaiah that we hear today. He can

picture the prophecy in all of its glory, so near and yet so far. He can

imagine the desert in bloom, the wide and holy highway that will funnel us all

safely into God’s loving arms, the burning desert sands turned into pools of cool,

clean water, the end of sickness and suffering, the end of despotic government,

everlasting joy and singing for the people of Israel. Like us, how John must

long for the freedom of God’s reign. He must yearn for the light of God’s

countenance to shine in the darkness. Is it enough just to urge him to be

patient? How do we find real meaning as we wait in our captivity?

Unlike

James with his platitudes, Jesus doesn’t fuss at John’s impatient question. When

the imprisoned John sends his followers out to track down Jesus and to ask him what

is going on, Jesus doesn’t say, “John, old cousin, get a grip. How dare you question

the Son of God!” Jesus doesn’t explain everything, either. He doesn’t give a

theology lecture on the problem of evil or on theories of salvation. He doesn’t

give John a blueprint of what will happen in the crucifixion and resurrection.

Jesus simply lists the healing acts that others have observed in his presence—healing

acts just like the ones that John remembers from that image in Isaiah. Jesus is

carrying out his ministry one small reversal at a time, and no one will see it

until the power of death itself has been reversed.

It’s

the same with Mary’s Song. The Magnificat doesn’t take on a preachy attitude.

It doesn’t even start with greatness. It doesn’t recite the lofty history of

Israel or recount the grand miracle of creation. It begins with one woman’s

amazement that God has come to her, a poor Jewish peasant girl from the Galilee.

Mary knows that her life has been nothing special. Mary begins with her own

experience, with her own experience of transformation from emptiness to

fullness of life: from girl to mother, from milking goats and hauling water to

speaking with angels, from shivering in the cold to being wrapped in the

loving-kindness of God, from lowly peasant to Mother of God.

Slowly,

as she speaks, her words shift from her own situation to the experience of her

people, from her own transformation to all of the times in Israel’s history

that God has lifted oppression, fed the hungry, punished the unjust, or raised up the poor. As Mary shares with her cousin

Elizabeth, it’s as if her words get away from her, radiating out across time,

gaining power and strength and meaning until the words themselves seem

to cause the transformations of which she speaks:

He has cast down the mighty

from their thrones, * and has lifted up the lowly. He has filled

the hungry with good things, * and the rich he has sent away empty. He

has come to the help of his servant Israel, * for he has remembered his

promise of mercy.

Meaning comes to Mary slowly—in a long history of insignificant people and

strange divine acts—and bursts forth in a slow crescendo as she remembers. Just

because we don’t realize what is going on until after the transformation occurs,

that doesn’t mean that God was not in what we perceive as insignificant

beginnings. Mary shows us that real meaning grows out of our own amazement,

that it must be discovered in reflection, in talking about our story with

others, and that it is true when it grows beyond anything that we can control.

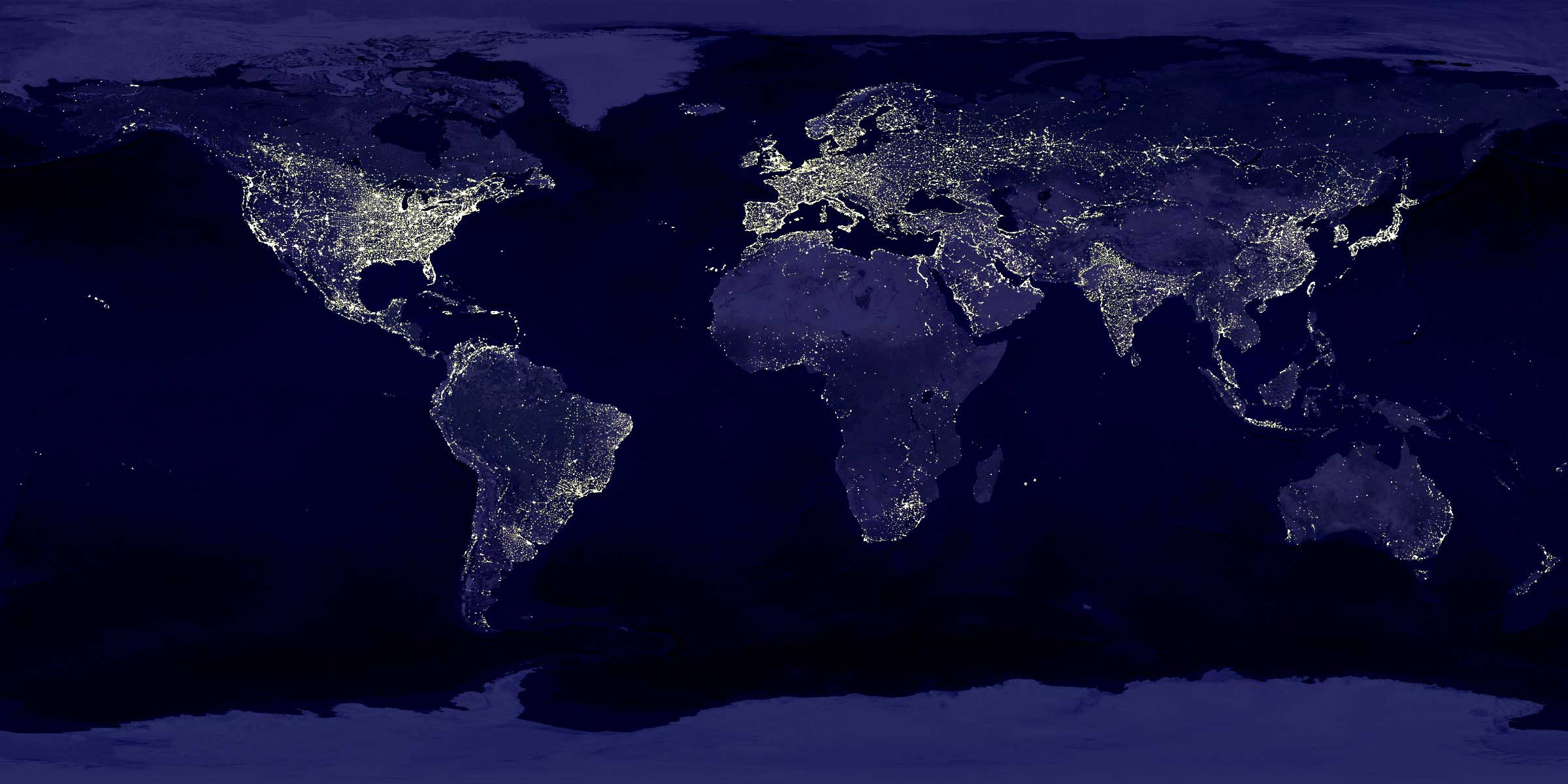

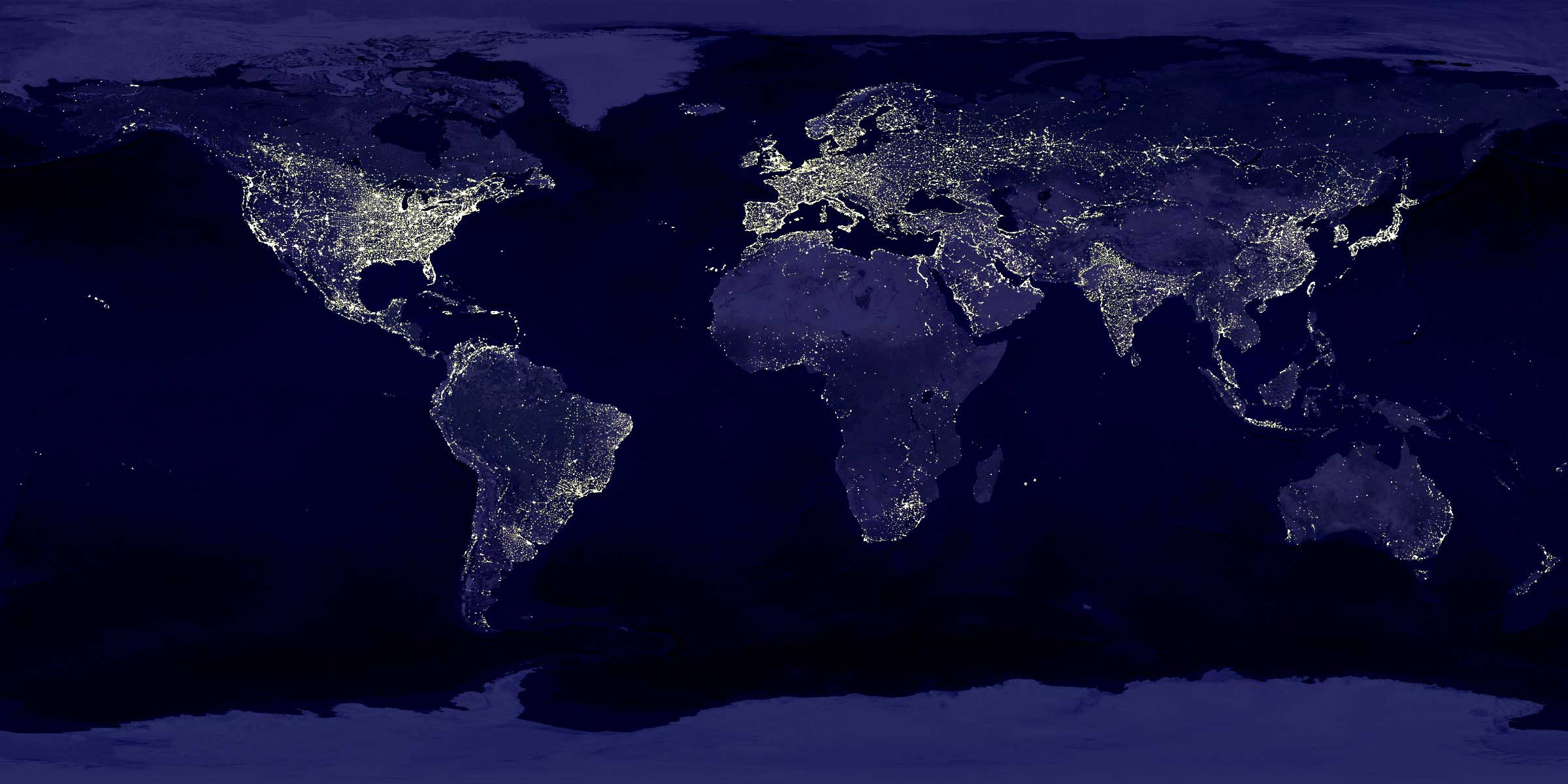

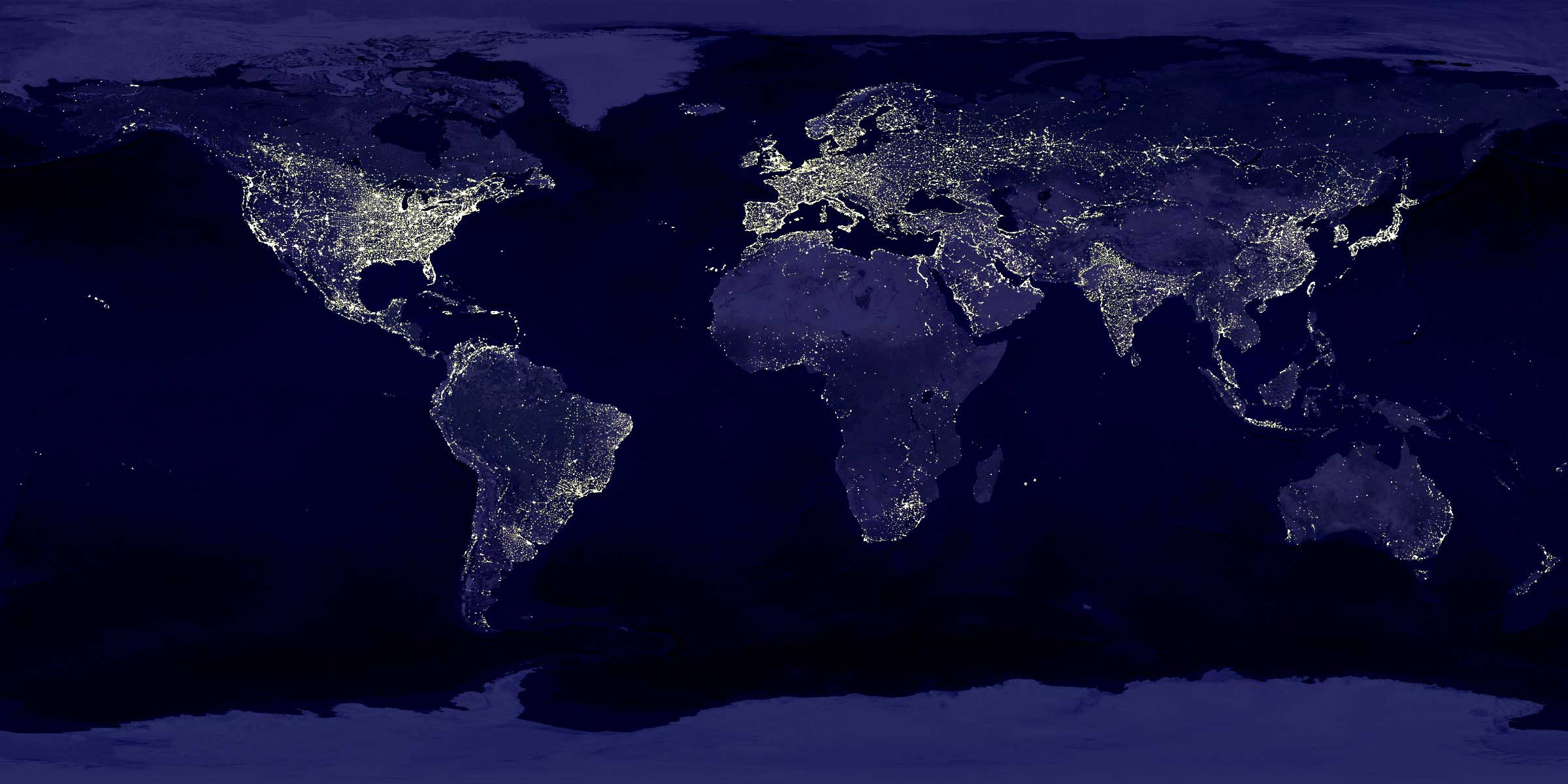

Think

about it: When we are impatient for change, doesn’t God come to us in small

particularities, like a narrow shaft of light into a dark room? Doesn’t God comfort

you in the love of a fellow human being who is as unique and irreplaceable in

this world as their own fingerprint? Isn’t God revealed in a certain landscape,

when the sun happens to come through the clouds in a certain way that might

never happen again were you to visit that place hundreds and hundreds of times?

Doesn’t God speak to you in a certain translation of a certain verse of

scripture, read at a certain time of day? Doesn’t God come to you when the

voices of the choir come together to touch your heart in just a certain way, in

just a certain moment? God comes to us in the particular. It is when we share those

particular experiences with others, when we incorporate them with our own story

and the story of our community, the meaning behind our waiting becomes

clearer—and then often blows us away.

As we wait in our own dark prisons this Advent—prisons of

fear, or illness, or dread, or loneliness, or powerlessness, or poverty, or privilege,

or even just in our prisons of impatience--it helps to follow Mary’s lead and

to let the particular accumulate in our hearts. As I think about my childhood

Christmases, all of my curious, impatient snooping for the object of my desire was

much more helpful than my sister’s nagging piety. God doesn’t want us to wait

in fear. God wants us to be out gathering bits and pieces of light: Shaking the

status quo, trying to peel back whatever covers the truth, poking into dark

corners, opening closets, rooting for God without ceasing, mapping out the Way.

So this Advent, I challenge us to go on a hunt: Gather the heartfelt smile at

the food pantry; the bit of childlike wonder; the quick prayer at the Advent

wreath; the song on the radio that fills just the right empty hole in your

heart; the flash of memory that sustains. Testify to transformation, no matter

how slow, no matter how lowly, and offer your testimony up to God and to your

neighbor. But be careful, you might just

find the Gift that God is hiding for you, and it will shake your world to

its foundations.

Image from piecesbypolly.com.

Image from piecesbypolly.com.